Central Pacific Edition

Emily Splashed

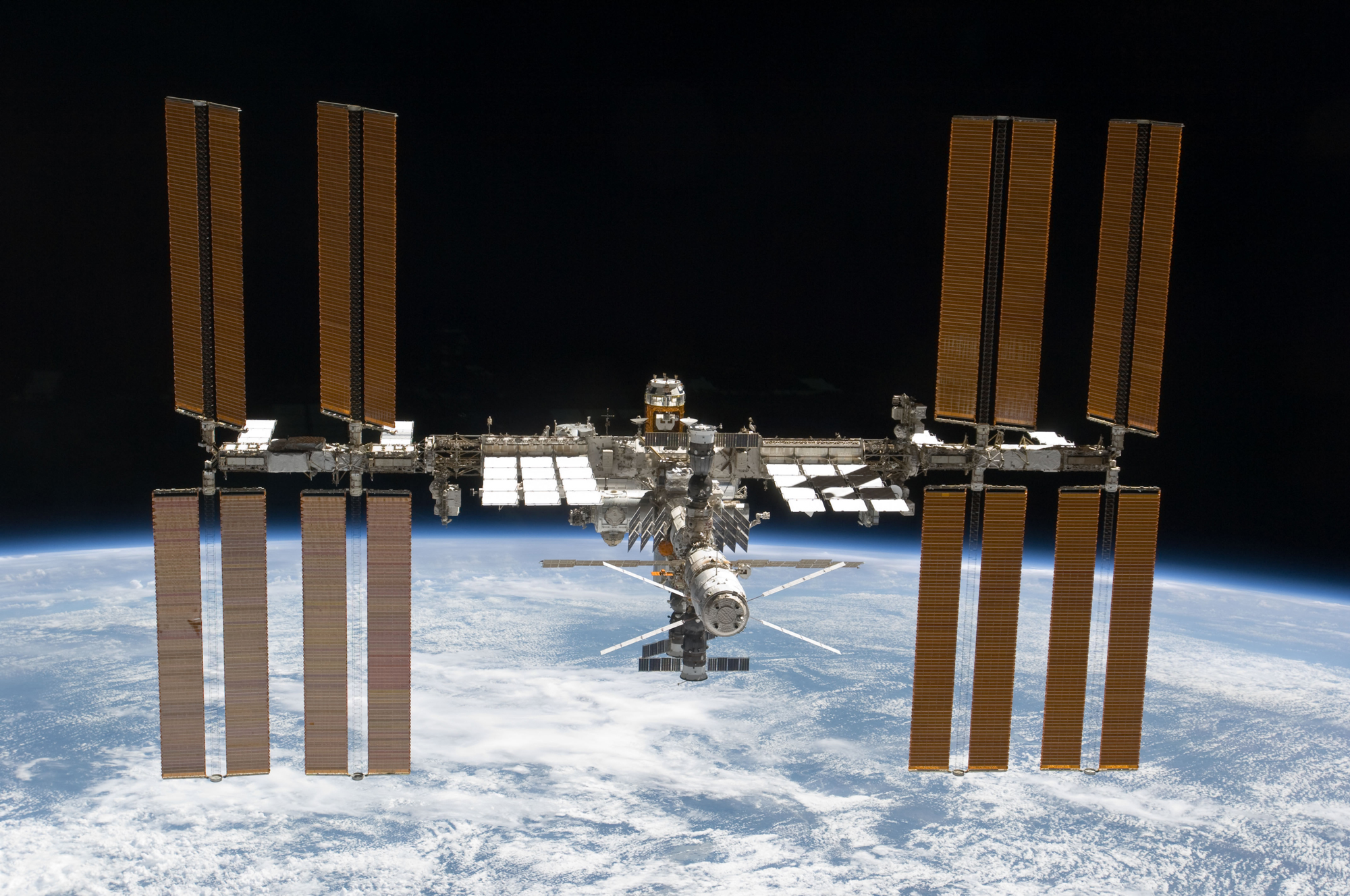

Action over Baker Island

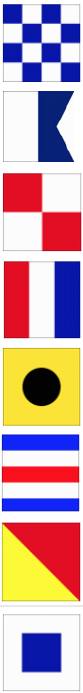

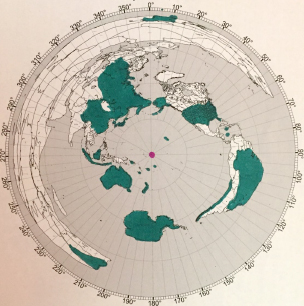

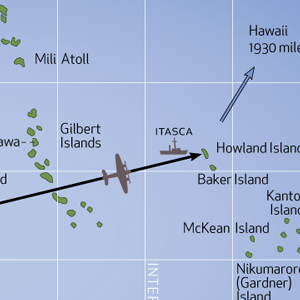

Baker is a small island just 37 nm south of Howland Island (where we are searching for Amelia Earhart’s Electra). In 1935, an attempt at colonization was begun on the two Islands, but the small settlements of four men each were evacuated in 1942 after Japanese air and naval attacks. Two of the colonists on Howland Island were killed in the attacks and buried there. In September of the following year, an airfield was established on Baker.

During construction, the Independence class light carriers USS Princeton (CVL-23) and USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24) provided air cover. Built on a cruiser hulls, the vessels each could carry more than 30 aircraft including squadrons of new F6F Hellcat fighters.

On September 1, 1943 a four engine Japanese flying boat, a Kawanishi H8K (known to U.S. forces as “Emily”) approached Howland Island from the west. Four F6 Hellcats were on CAP (combat air patrol) over the Baker airfield construction operations and were vectored to the bogey by the FDO (fighter director officer) on board the radar-equipped destroyer USS Trathen (DD-530). The unsuspecting Emily was detected at a range of over 30 miles and was taken completely by surprise. Passing just south of Howland at 7,000 feet, the Japanese plane had apparently completed its reconnaissance and reversed course to head back west when a Hellcat piloted by Lt. (j.g.) Richard Loesch descended out of the sun from 10,000 feet and opened fire with its six 50-caliber machine guns. On the heels of that attack was wingman Ens. A. W. Nyquist in a second F6 who made a similar run at the enemy. Closing to within 100 yards, the fighters fired 300 rounds each into the Emily which made no defensive maneuver. Streaming gasoline, the plane was seen to descend in a slow spiral until it hit the water and exploded in flames. No survivors were observed. This was the first combat action of an F6F Hellcat, which replaced the F4F Wildcat as the primary U.S. carrier based fighter of the Pacific war.

The enemy plane was shot down so suddenly it failed to send a radio report. Two days later a second Emily was picked up on radar about 20 miles from Baker at 8,000 feet and the CAP aloft was dispatched, this time operating from the carrier Belleau Wood. Four F6 fighters sped to the scene. Attacks were again made from above, but this time the Japanese plane was able to take evasive action. Racing for cloud cover, the damaged aircraft was able to escape and contact was temporarily lost. However, one of the fighters flew around the clouds and spied the flying boat at a lower altitude. Two others jettisoned their belly fuel tanks to gain speed and took up the pursuit. Catching the enemy at a distance of 50 miles from Baker, the F6’s piloted by Lt. (j.g.) Coleman and Ens. E. J. Philippe pressed the attack. The Emily appeared to be making a water landing when it exploded, burned, and sank. No survivors were seen.

A third Emily was shot down by planes from Princeton on September 8. Apparently, none of them were able to get off a radio report to their base in the Gilberts owing to the quick action of the Hellcats. The carrier Princeton subsequently met her end at the Battle of Leyte Gulf on October 24, 1944 when a single bomb from a Japanese “Judy” dive bomber penetrated the flight deck and exploded in the hanger, causing fires and further explosions. Other ships rendering assistance were caught in secondary blasts causing many casualties. 108 men of the crew of over 1,400 were lost; the cruiser Birmingham got the worst of it with 233 men killed and severe damage. Three other ships suffered lesser damage. Princeton was scuttled with torpedoes that afternoon.