Central Pacific Edition

Mission Conclusion

Nauticos Crew Head Home, Makes Plans

Today the Eustace Earhart Discovery Expedition 2017 comes to a close. Yesterday I took the opportunity to thank Alan and the rest of the team that made it happen, and I am sincerely grateful for the privilege of sailing with everyone. Captain Noe and the crew of the good ship Mermaid Vigilance came to our last operations meeting and thanked each of us one by one with handshakes, high fives, and hugs. After just a few weeks together we feel like old friends, and I was truly touched.

Today the Eustace Earhart Discovery Expedition 2017 comes to a close. Yesterday I took the opportunity to thank Alan and the rest of the team that made it happen, and I am sincerely grateful for the privilege of sailing with everyone. Captain Noe and the crew of the good ship Mermaid Vigilance came to our last operations meeting and thanked each of us one by one with handshakes, high fives, and hugs. After just a few weeks together we feel like old friends, and I was truly touched.

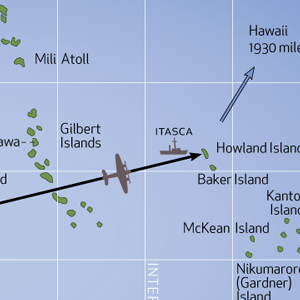

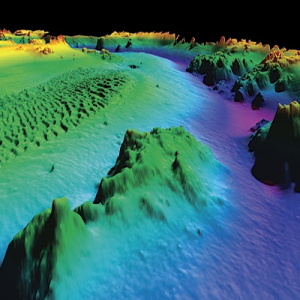

As you may have gathered, I cannot announce that we found the Electra. However, it’s worth focusing on what we did accomplish. We covered 725 square nautical miles this expedition, a record for Nauticos. Our tally in three expeditions is nearly 2,000 square nautical miles, and with the coverage by the Waitt Foundation in 2009 we’ve mapped an area the size of Connecticut at 1 meter resolution or better. This is one of the largest contiguous areas of the deep ocean mapped in history. We have discovered seamounts, calderas, and volcanic cones never seen before. We mapped a large portion of the Howland and Baker Islands Marine National Monument, and helped guide NOAA’s recent expedition to the region on Okeanos Explorer. The new data will be provided to geologists and other scientists in the near future.

Expedition performance was exemplary, including our Nauticos team, WHOI, the ship, and all support elements. We completed the 1,800 square mile high probability search area we set out to cover in 2002. Alan said, “You and the team have done everything you said you would, and the equipment and people performed near flawlessly. No reason to hang your head low.We either missed it somewhere or just didn’t cover the right spot.”

Of course, analysis always leaves residual possibilities, even without altering assumptions, and the source data hasn’t changed. We also have very valuable new search coverage to consider. The technology we used to search the seafloor has improved with each expedition, and we look forward to future work with WHOI using next-generation AUVs.

We will take another look at all of our work, and have already made a to-do list. We will return home, take a well deserved rest, then get back to it!

— Dave Jourdan