Central Pacific Edition

Re-Supply Mission

Vigilance Hooks Up with S/V Machias

Being an oceanographer is not quite the same as being a professional sailor. Oceanographers have the best of two worlds – both the sea and the land. Yet many of them, like many sailors, find it extraordinarily satisfying to be far from the nearest coast…”

Being an oceanographer is not quite the same as being a professional sailor. Oceanographers have the best of two worlds – both the sea and the land. Yet many of them, like many sailors, find it extraordinarily satisfying to be far from the nearest coast…”

— Roger Revelle (1909-1991)

Yesterday we welcomed the good ship S/V Machias built in the State of Maine and operated from Honolulu. We learned that skipper and owner, Cap’n Bill Austin, is a well known representative of both the sea and land worlds and precisely the kind of person we needed for a mission to our remote location.

His crew of three are seasoned seamen who are fiercely loyal and confident in their captain. All of which builds our confidence in the intrepid team.

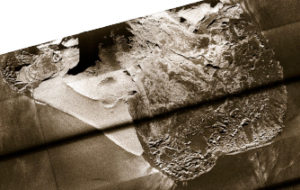

Machias is an eighty-two foot Maine-built steel-hull, stay sail schooner, registered as a freight carrier and operating out of Honolulu. With a long history of educational work for the University of Hawaii and the Honolulu public schools in past decades, it has been part of the community and is still engaged in whatever venture puts her to sea.

According to Mary Crowley, the word “Machias” roughly translates in the Native American Passamaquoddy tribe language as “little bird on big water,” a reference to the Machias River in Maine. Machias is known as the site of the second naval battle in the American Revolution. In his History of the Navy of the United States of America, none other than James Fenimore Cooper dubbed this engagement “the Lexington of the Seas.” The battle, which occurred in June 1775 at Machiasport, began after townspeople refused to provide the British with lumber for barracks. This led to the capture of the armed schooner HMS Margaretta by settlers under Captain Jeremiah O’Brien and Capt. Benjamin Foster.

Aboard Machias was precious cargo important to our mission, specifically ten glass spheres used as deep sea floats for transponders, and two replacement transponders used for underwater navigation. There were also some treats for the teams living and working aboard the Mermaid Vigilance: chocolate, macadamia nuts, and a few other delights.

The re-supply mission was organized in some haste on March 6th as a rash of float failures (a very unusual occurrence) threatened to stall our expedition before it had hardly begun. With a normal inventory of eight pairs plus spares, the REMUS team was down to five operating units early on and four before the resupply arrived. Fortunately, the team managed to juggle the available units with little loss of survey time. Offered a bonus for quick response, Cap’n Austin organized a crew and took on supplies for a three-week sea voyage in just a few days. His cargo arrived from Massachusetts and was carefully packed on board with help from the University of Hawaii Marine Center. Machias got underway on March 12th for a 10-day transit. Mary Crowley of Ocean Voyages helped setup the charter.

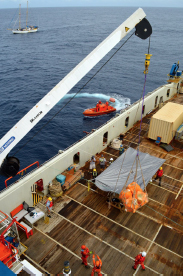

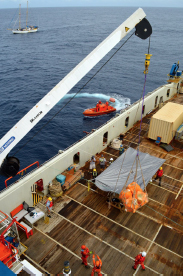

Cap’n Joe organized the deck crew and rehearsed the event the day before. It was a busy morning as Machias came in sight around 0800, just as REMUS OPS was launching the AUV.

Cap’n Noe took charge of the ship’s launch, known as the FRC (Fast Response Craft) and fetched the cargo in three trips back to Vigilance, where it was hoisted aboard by crane. The operation went very smoothly and soon Machias reversed course and headed back home.

Our own Cap’n Joe has small acquaintance with land, but while at sea he appears to have no aversion to treats.

— Charlotte Vick

And thanks to Charlotte for a tremendous job getting this important mission off the ground in such short order!

— ed.