Central Pacific Edition

Shooting the Stars

The Arcane Art of Celestial Navigation

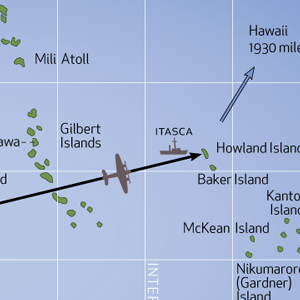

On our last expedition Spence had the idea that he and I (with part-time help from many other folks) should navigate to Tarawa using only the ship’s course by compass, speed by engine setting, and the sky. No GPS or other electronic means, other than using the clock for accurate time. This is more or less equivalent to the state-ofthe- art of navigation around the time of World War II, and it’s useful as an exercise because we often deal with data from that era. It’s also fun in a nerdy sort of way.

On our last expedition Spence had the idea that he and I (with part-time help from many other folks) should navigate to Tarawa using only the ship’s course by compass, speed by engine setting, and the sky. No GPS or other electronic means, other than using the clock for accurate time. This is more or less equivalent to the state-ofthe- art of navigation around the time of World War II, and it’s useful as an exercise because we often deal with data from that era. It’s also fun in a nerdy sort of way.

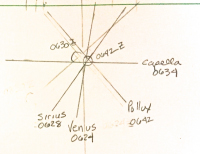

I found that being an old-time ship’s navigator was a full-time job (and I wasn’t standing watches during the transit). A lot of it involves “shooting a fix,” using a sextant to measure the altitude (height above the horizon) of a star, sun, moon, or planet, and using tables of orbital data to calculate a ship position. The sextant works by projecting an image of a part of the sky onto another image of the horizon, with an adjustment to move the projected image in altitude. You adjust until the image of the star just touches the image of the horizon, and read the angle between the projected images off the dial. You can measure reliably down to one arc-minute (1/60th of a degree) using this instrument.

The basic principle is simple. Through astronomical observations, we know very accurately the positions of the stars, sun, moon and planets at any time. We can project the location of a particular object onto the surface of the Earth at any particular moment, known as the Geographic Position (GP). If we are at that exact position, that object would be directly overhead (that is, at an altitude of 90 degrees). If we are away from that point, the altitude will be lower, and we can use the observed altitude (measured with the sextant) to compute our distance from that GP. If we plotted the GP on a globe, and drew a circle around it with radius equal to that distance, we would be somewhere on that circle.

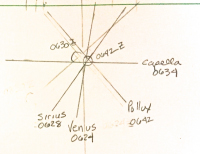

In practice, since we have some idea where we are in the world, we only need to draw the part of that circle that passes near our assumed location, which is a “line of position” (LOP). If we do this with three or more objects, we get several lines, all of which should pass through our position, and when we plot them, we get a position fix. Of course, there are lots of details to correct for, and the computation itself is a bit arcane, and time consuming.

Well, we found Tarawa last expedition, and heady with success, we decided to try our hand at some star fixes out here. The results were pretty good as we got an excellent fourstar fix that compared beautifully with GPS. However, it took us about 3 hours of ciphering and most of an eraser to puzzle out the answer. We’ll give ourselves a B+.

OPERATIONS SUMMARY:

Vehicle Mission 06 has REMUS on deck at 0500 for a routine turnaround service. Deck teams will be busy in the morning. REMUS will start mission 07 late in the morning. SEA School and the Daily Progress Report will be held in the afternoon.