Central Pacific Edition

Marshall Islands: The Little Trade

More excerpts from “My Return to Majuro”

Yesterday Cap’n Spence related his exploits in the Marshall Islands commanding USS Brunswick in the Pacific. The saga continues….

Like I said before…it was the spring of 1989. I commanded the Navy salvage ship USS Brunswick at the time based out of Sasebo, Japan. We were still savoring our good fortune: an assignment to visit the Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands was special. This was an assignment that I had experienced twice before as a junior officer, and the memories were still vivid . The big difference this time; knowing what was ahead, I was ready able and willing to apply that knowledge in some way to make a difference. I didn’t yet know what form it would take.

Like I said before…it was the spring of 1989. I commanded the Navy salvage ship USS Brunswick at the time based out of Sasebo, Japan. We were still savoring our good fortune: an assignment to visit the Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands was special. This was an assignment that I had experienced twice before as a junior officer, and the memories were still vivid . The big difference this time; knowing what was ahead, I was ready able and willing to apply that knowledge in some way to make a difference. I didn’t yet know what form it would take.

Our sister ship across the pier, USS Beaufort (ATS-2) was also in port with us, a rare occurrence. We were of ten scattered across the western Pacific, usually in opposite directions, but hardly ever together in our home port. Their commanding officer was a longtime friend and neighbor of mine, and we met one morning for coffee.

I detailed the itinerary of our assignment to TTPI for him. We talked about some ideas on where to stop and dive in the beautiful lagoons, and make the most of this great assignment. He said, “you know, I have a sailor from one of those countries. Let me check on that.” And sure enough, Beaufort had a young enlisted man onboard who listed his home as the Federated States of Micronesia. The idea came to me immediately: “Would you like to make a trade? I’ll take your sailor from FSM with me to TTPI, and in exchange I’ll leave a sailor of equal grade and qualifications.” This is called “cross-decking” and is done frequently. We both agreed that we would make the offer to our sailors. I was pretty sure the Micronesian sailor would agree to this. But where was I going to find a volunteer of equal grade and qualifications? There was only one way to find out . T h e executive officer posted a notice in the Plan of the Day: “Any engineering petty officer having X training and Y qualifications who chooses to stay in Sasebo aboard our sister ship, Beaufort instead of deploying to the South Pacific, please notify the executive officer.” There were probably only a few who would even qualify for this deal, let alone someone who wanted to stay behind. I was not hopeful for this. But in a few days, a sailor stepped forward. A young man with a wife and infant child at home was a volunteer for the swap. Across the pier, the Micronesian sailor was a volunteer. Let’s Make a Deal!

The configuration of the two ships was identical, the organization of the ship’s crew standardized, the general shipboard routine the same. The swap happened the day before we sailed.

Reporting aboard for duty was Engineman Third Class Reiche, (RAY-chee) USN. I did not make a big deal about where his home was. I welcomed him aboard like any other sailor, and he fit right into his new ship easily. We waved our final good byes to our families and friends, and pointed the bow East by Southeast, bound for TTPI.

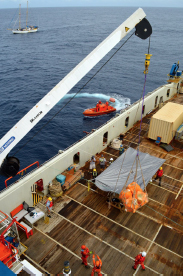

Our first stop was Guam. This was headquarters for the naval administrator for TTPI. There were lengthy documents to read on the purpose of the trust territories, policies regarding ship visits, and implementing instructions on how to accomplish all of it. I understood it well. It had been four years since I was last there. While technically under the Geneva Conventions, our salvage ship was considered a warship. But if you look closer, where large naval guns would be placed, we had deck cranes. Where torpedo tubes or depth charge racks should be mounted, we had diving stations. We did not possess any offensive war making capabilities. We didn’t appear threatening. We were a small and maneuverable vessel. For that reason, we were well suited for visiting small nations, showing the flag, painting sclools o r orphanages, which we were glad to do. On the day we departed Guam, I called EN3 Reiche to the bridge. My purpose was to get a little better acquainted with him. He was polite and shy, and his answers were short. Maybe he had never been on the bridge before? After all, he was a “snipe.” That was the colloquial name we used for engineers because they work below the main deck, a place with no sunshine. And there were two kinds of snipes: The hole snipes work in The Hole, the colloquial name we have for the engine room. Hole snipes considered themselves elite among the other snipes, which we called fresh air snipes. These engineers worked anywhere outside of The Hole and took care of auxiliary machinery like boat engines, cranes, winches and compressors. Reiche was a fresh air snipe , and he was totally comfortable on the bridge. He told me that he grew up on the water.

… to be continued tomorrow